The Unexpected Consequences of a Robust AAC Device

Our family had the amazing opportunity to attend Camp Alec Family Literacy Retreat. It was an incredible weekend. But I left perplexed about something that I couldn’t easily put into words during camp to discuss with the directors, literacy coaches, or Drs Karen Erickson and David Koppenhaver. As we drove down highway 55 from Chicago to St. Louis, I had a growing unsettledness about the overlap of what I heard at camp and what I knew about Nathaniel.

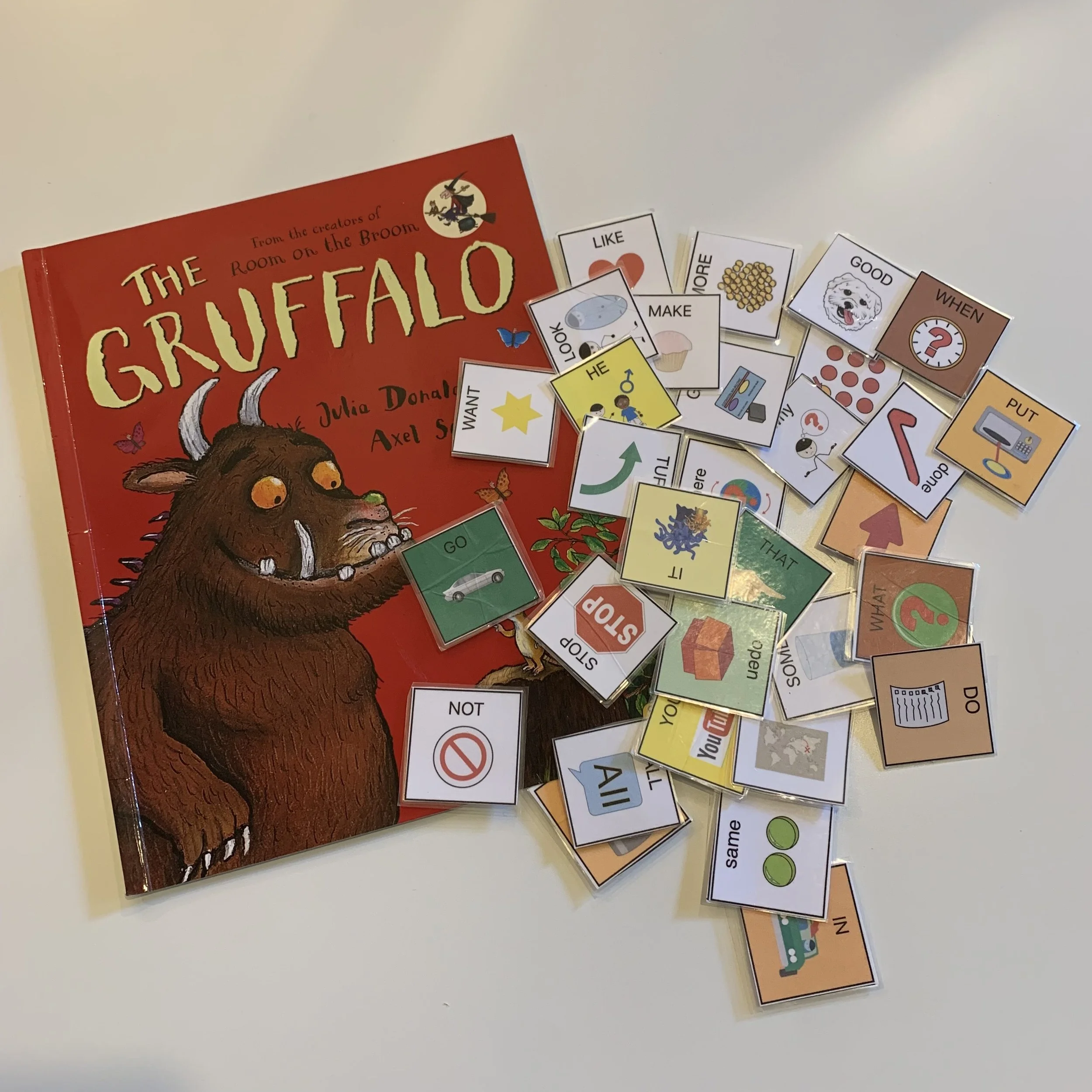

Nathaniel uses a robust AAC system. He has about 1,300 words open. With the toggle of one button he has access to over 15,000 words. He uses this feature and a variety of other built in aids to communicate. He uses his device spontaneously and with a wide variety of people. He knows his device’s organization and categories. He comments, questions, relays past events, jokes, requests, tattles, plans for the future, and demands with his device. He’s strategic in using the words he has to say words he doesn’t have. “Green superhero man crash” is his go-to phrase for Hulk. I’ve observed Nathaniel speak to strangers, who after hearing that inital description and asking a couple clarifying questions, have understood fine. When they don’t, Nathaniel persistently adds more words.

But he doesn’t spell HULK on his device’s keyboard. And that was noticed at the literacy camp.

I’ve purposefully not programmed the word HULK into the device. Some speech therapists may question that decision, but I want him to use what I’m teaching him about the alphabet. I model the spelling. He returns to his prolific word options either unmotivated or unable to spell.

This is what unsettles me on the drive home. Repeatedly over the weekend I heard people mention that it is frequently the limitations of an AAC device, or never having one, that motivates a child to use the twenty-six letters to communicate. Is an unexpected consequence of providing Nathaniel a robust AAC device and good intervention now that he has low motivation to use the alphabet to spell words he doesn’t have? If yes, is that a negative thing? I spend miles in the passenger seat on the drive home pondering these questions. It feels a little like I’ve done well in an endurance event called “AAC intervention,” but now question if that was the event I really should have entered.

A few days into my musing on the same questions, I suspect the answer to the first question is yes. As Nathaniel’s primary communication partner and the person who spends hours a day with him, I do think that Nathaniel’s robust AAC device means he is going to be less motivated to use the alphabet to communicate than an individual with fewer words available. But I think the answer to the second question is no. This unexpected (to me) consequence of his robust AAC device isn’t a negative thing.

I am hemmed into my family between a math teacher father, a brother with a PhD in math, and a daughter who started her undergraduate in engineering. Perhaps due to their influence, I visualize Nathaniel’s communication journey as two lines or paths. One path is what he communicates using his device - the programmed in phrases, words, and bits of words like endings s, er, or est. The second path is what he communicates using only letters. Currently the paths appear to be train tracks - running parallel. Except they are not parallel; they don’t have the exact same mathematical slope. They are a degree or two off from each other. They are slowly converging. Way in the distance, at a place too far to be seen now, these two paths will intersect. That point has a label. It is not point A or point B like we remember from Geometry class. The convergence of using the device to communicate and using the alphabet to communicate is a point labeled: “I can say whatever I want to say, to whomever I want to say it, whenever I want to say it.”*

I can’t see that point for Nathaniel. I can’t know what ideas he’s going to want to say with his device as whole words or combinations of words and what ideas he’s going to spell to communicate. And so it follows that I can’t provide only literacy instruction or only device use interventions and modeling. This realization matters as I arrive home late on the Sunday night after camp and have to teach and parent on Monday morning from a place of understanding and conviction. Nathaniel needs both his robust device and the alphabet to continue down the paths towards that point of full communication. Karen mentioned during the retreat that the adult AAC users use their programmed words for about eighty percent of their communication. They spell for the remaining twenty percent. Nathaniel needs to learn to read and write so he can say one hundred percent of what he wants to say, not just eighty percent. Eventually what ideas fall into the eighty-twenty split will not be mine to decide. Ultimately, but only through using the alphabet, he will determine what words to program into his device. He will do the programming. What Nathaniel doesn’t yet grasp is that learning to spell HULK is what will give him more control and the decision making power to use it as a word or to spell it.

Camp weekend tumbled into Monday and on the way home from a late afternoon playground visit, Nathaniel called my name using his device from the backseat.

“Yes, Nathaniel?”

“Buy Andrew birthday gift red and blue superhero toy.” Nathaniel’s brother, Andrew, is turning thirty in a couple weeks. Nathaniel must have overheard his Dad and I talk about a gift for Andrew on the drive home the day before. I suddenly realize that I can use communication break downs to show Nathaniel his need for clarity and perhaps that clarity could come from the alphabet.

“Hey Nathaniel,” I start. “I know two superheroes who have red and blue costumes. Are you thinking of Captain America or Spiderman? Can you tell me the first letter of the superhero’s name?”

“C,” he answered quickly from the backseat. With more exchanges, he confirmed that he thinks Andrew wants a Captain America toy for his thirtieth birthday present from this parents.

Yes! That worked! He was motivated to use the alphabet to help his communication!

Then on Tuesday morning at breakfast Nathaniel said, “Today buy Andrew birthday gift red and blue superhero toy not spider man.” He used “spider” from the device’s insect page and “man” from the people page to create the compound word. In so doing, he negated what he likely anticipated would be my question sending him to the alphabet. His robust device and his skills using it give him this communication opportunity. Right now, this is easier than using the alphabet. That tells me something about his developmental stage and the instruction he yet needs.

At the retreat, David said good teaching matters. He said if a child like Nathaniel doesn’t learn to read and write, it is the teacher’s failure not the child’s. I probably heard David say that in Cleveland in 2019. I know I believed it before I went to Michigan last weekend. It’s why I went to Michigan - to gain insight on how to be a better teacher for Nathaniel. Good teaching is hard work. It is always an endurance event. In some ways providing instruction that grows Nathaniel’s use of the alphabet despite his good device understanding and communication feels like moving a railroad tie an inch closer to the one running a few feet away. But I know as long as those paths have even slightly different slopes, they will intersect someday in the future at that full communication point I am aiming towards.

*a quote by Dr. David Koppenhaver that I heard at Comprehensive Literacy Instruction training in Cleveland in March, 2019.

It should be noted that Nathaniel and parents did find a Captain American super hero action figure for Andrew. We gave it to him at his birthday party this last weekend.